4.14 Welcome to the World of Mycoses (contributed by Pamela Appleby, 2004)

This mycoses page is intended to give students (or anyone who's interested really!) some insight into the clinical aspects of mycology. This page covers an area of mycology which is more immediately interesting to most people.

Here you'll find details of diseases, the organisms that cause them, symptoms, and treatments. Hope you find the journey useful.

Mycology is the study of fungi; medical mycology is the study of fungi which cause

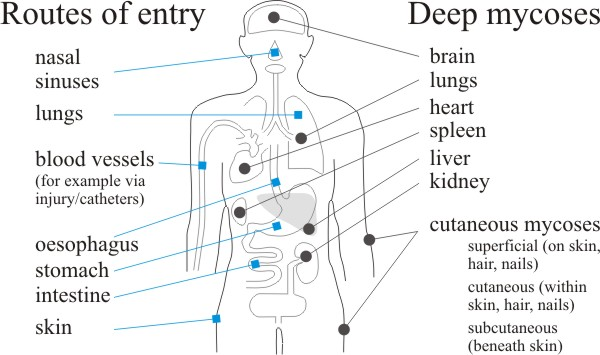

disease in man. The fungus diseases of humans are called mycoses and the majority, perhaps all, are not caused by dedicated pathogens, but rather by fungi common in other situations that take advantage of a particularly beneficial set of environmental conditions or of a host with defences weakened in some way (so-called opportunistic pathogens). There are about 400 fungal pathogens that cause diseases of humans and domestic animals, and only about 60 species of fungi cause disease in humans; of these about 30 cause superficial infections of the skin and about 30 cause subcutaneous, lymphatic or systemic infections (Fig. 1) together with several other species that cause allergic reactions.

Different diseases can affect different groups of people, in different areas of the world, causing a huge range of symptoms, ranging from rashes, ulcers and abscesses, to lung problems, pneumonia, meningitis, and in the severest cases, death. Fungal diseases are most serious and life threatening in AIDS patients and those with immune dysfunctions. In these cases a mild common fungal infection can lead to death. Some fungi are associated with and transmitted by animals (pets as well a swild animals), others by contact with other humans. Some cause highly virulent infections, others cause a mild disease which resolves itself.

The fact that there is a relatively short list of mycoses does not mean that fungus diseases of humans are rare. What the human disease fungi lack in diversity, they make up for by being very widespread. Many people (?everybody?) suffers from athlete’s foot at some time in their life. This is caused by a tropical import called Trichophyton rubrum, but you don’t have to go to the tropics to collect your share because it so likes warm and moist shoes that it is now distributed throughout the temperate climatic zones and is so common that you can be infected very easily. Athlete’s foot is little more than a nuisance though, as it can be successfully treated with over-the-counter remedies.

Generally speaking, we are prone to fungal invasion of the skin, nails and hair because they are exposed to the environment. Athlete’s foot is one example, ringworm is another such infection. This introduces another aspect of fungal biology: ringworm is a family of mycoses because the cause can belong to one of two closely related genera, Microsporum or Trichophyton. Each fungus is very specific to a particular part of the body. A range of animals can also suffer ringworm diseases of skin and fur, and that range includes farm animals and pets. The fungi spread readily to humans, which introduces another notion, that of a zoonosis, being a disease that can be transmitted from other vertebrate animals to humans.

|

| Fig. 1. Routes of entry and distribution of the fungus diseases of humans. Labels at left indicate routes of entry of pathogenic and opportunistic fungi that cause deep and cutaneous mycoses. At right we indicate the principal tissue sites of deep mycoses in comparison with superficial, cutaneous and subcutaneous mycoses. From Moore, Robson & Trinci (2011). |

Another remarkable statistic about human mycoses is that it is now unusual for a woman to go through her reproductive years without at least one significant infection by the yeast Candida albicans. This introduces another source of disease because C. albicans is a normal inhabitant of the human mouth, throat, colon and reproductive organs. Usually it causes no disease but lives commensally in ecological balance with other microorganisms of the digestive system. However, other factors such as diabetes, old age and pregnancy, but also hormonal changes, can cause C. albicans to grow in a manner that cannot be controlled by the body’s defence systems and candidiasis results, with symptoms ranging from the irritating to the life-threatening. For most people candidiasis, like other superficial infections, is irritating; the fungus remains in the outer layers of the skin because the body’s immune defence system prevents the fungus penetrating more deeply. In patients whose immune systems are compromised in some way there is no such defence and the infecting fungus becomes deep-seated, systemic and potentially fatal.

This category of patient includes transplant patients, where the immune system is pharmaceutically modulated to control rejection, and people with AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome), where deterioration of the immune system is caused by the decline in CD4+ T cells, the key infection fighters of the immune system, by the HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) retrovirus. Infections of those with weakened immune systems are called opportunistic infections. Candidiasis is the most common HIV-related fungus infection that can affect the entire body, but there are other opportunistic fungi that typically do not cause disease in healthy people but only those with damaged immune systems; these fungi attack when there is an ‘opportunity’ to infect and can cause life-threatening disease.

Classification of disease types caused by fungi can be difficult and many sources of information classify them in different ways: fungi can be divided according to the ways they cause disease, or the level of damage they cause to the host, or classified according to the group of fungi to which the disease organism belongs. The fungi discussed on this page are classified according to the infection they cause, to try to keep things simple.

There are five types of mycoses to describe, in two main categories:

- skin mycoses

- superficial mycoses

- cutaneous mycoses

- subcutaneous mycoses

- systemic mycoses

- systemic mycoses due to primary (usually dimorphic) pathogens

- systemic mycoses due to opportunistic pathogens.

Resources Box Click here to visit a page that completes the description of these five types of mycosis |

Additional information

An excellent online source of information about human fungal infections (which we have dipped into frequently for help with this text) is Doctorfungus.org, which can be consulted at this URL: http://www.doctorfungus.org.

Updated December 7, 2016